Why I Became a Counsellor

People often ask me why I became a counsellor or therapist. Honestly, I’m not entirely sure, I feel I was gently pushed in this direction.

My undergraduate studies were in Arabic and Islamic Studies at Al-Azhar University in Cairo (Egypt). It was a four-year programme that immersed us deeply in the Islamic scholarly tradition. Living in Cairo meant this wasn’t just something we studied; it was something we lived. Mosques were alive with advanced study circles, teachers explaining classical texts, and a strong sense of continuity with our heritage. Walking through the streets around Al-Azhar often felt like walking through history. I felt this greatly shaped my identity; my habits of reading books, intellectual curiosity, and the sense that I need to continually develop were very much shaped there.

When I returned to the UK, the transition was disorientating. I often asked myself: what do I do with all this knowledge now? No one was going to ask me about chains of narrators in hadith or complex concepts in Usul al-Fiqh. The community I came back to was facing very different struggles; emotional, relational, and psychological.

From Study to Service

I went on to complete three years of postgraduate study: an MA in Islamic Studies at the University of Aberdeen with a thesis on temporary marriage in Sunni and Shi‘i traditions, a Master’s in Philosophy at the University of Glasgow with a thesis on the Euthyphro dilemma in moral philosophy, and a Diploma in Contextual Islamic Studies and Leadership at Cambridge Muslim College. Of these, the Cambridge diploma was perhaps the most relevant and enjoyable. It was practical, community focused, and bridged traditional learning with real life leadership.

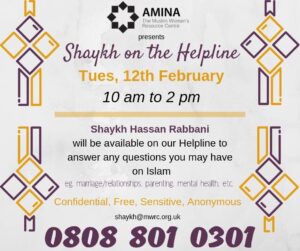

Alongside my studies, I did a range of work. I was a panelist on BBC radio talk shows, took part in interfaith events, taught Islamic Studies to adults, and was involved in a Glasgow project called “Shaykh on the Helpline.” Once a month, women of faith would call to share problems and seek advice. I had no formal counselling training then, but I listened and responded as best I could.

One call has always stayed with me. A sister disclosed horrific sexual abuse and explained that her abuser had married her sister. “Will I get justice in the hereafter?” she asked. I sensed she already knew the answer. What she needed was a space to process what had happened. That call left a lasting impression.

I felt it was way out of my depth. My scholarly training did not equip me to deal with trauma or to hold a safe space in which a person could be listened to with deep empathy. I realised then that I needed further training.

The Turn Toward Counselling

By 2016, back in Glasgow, I was asking myself what to do next. Counselling had never been the plan, but my work made me realise I needed to upskill. As a scholar, I also attend many Nikahs, and over the years, couples would approach me with relational issues long before they ever considered therapy.

At one wedding I sat next to a CBT therapist. We spoke for two hours. I was fascinated by the overlap with Islamic spirituality. He even linked ideas back to our tradition. I went home inspired and applied for the COSCA Counselling Skills Certificate, my first formal step into counselling.

The course ran once a week for a year and was a real eye opener. The class was diverse, medics, social workers, lecturers, all wanting to improve listening and empathy. I was the only Muslim. I especially loved the triad work, counsellor, client, observer, which was practical and reflective.

After COSCA, a bigger decision followed: what kind of therapist do I want to become?

Why Relationship Counselling Made Sense

Around that time I had also become a Muslim Chaplain at Heriot Watt University, professionally based in the Wellbeing Centre. Being surrounded by counsellors and attending wellbeing meetings gave me a window into how the profession actually works and entails.

When I looked at training routes, CBT, person centred, Gestalt, I felt overwhelmed. But one pathway immediately made sense, a Diploma in Relationship Counselling.

It felt like the right bridge between my background and the reality I was seeing in the community. For years, as an Imam in Glasgow and Edinburgh, I had often been an informal mediator for couples. This training would allow me to do that work professionally, with structure, theory, and accountability, not just good intentions.

Diploma in Relationship Counselling (Relationships Scotland)

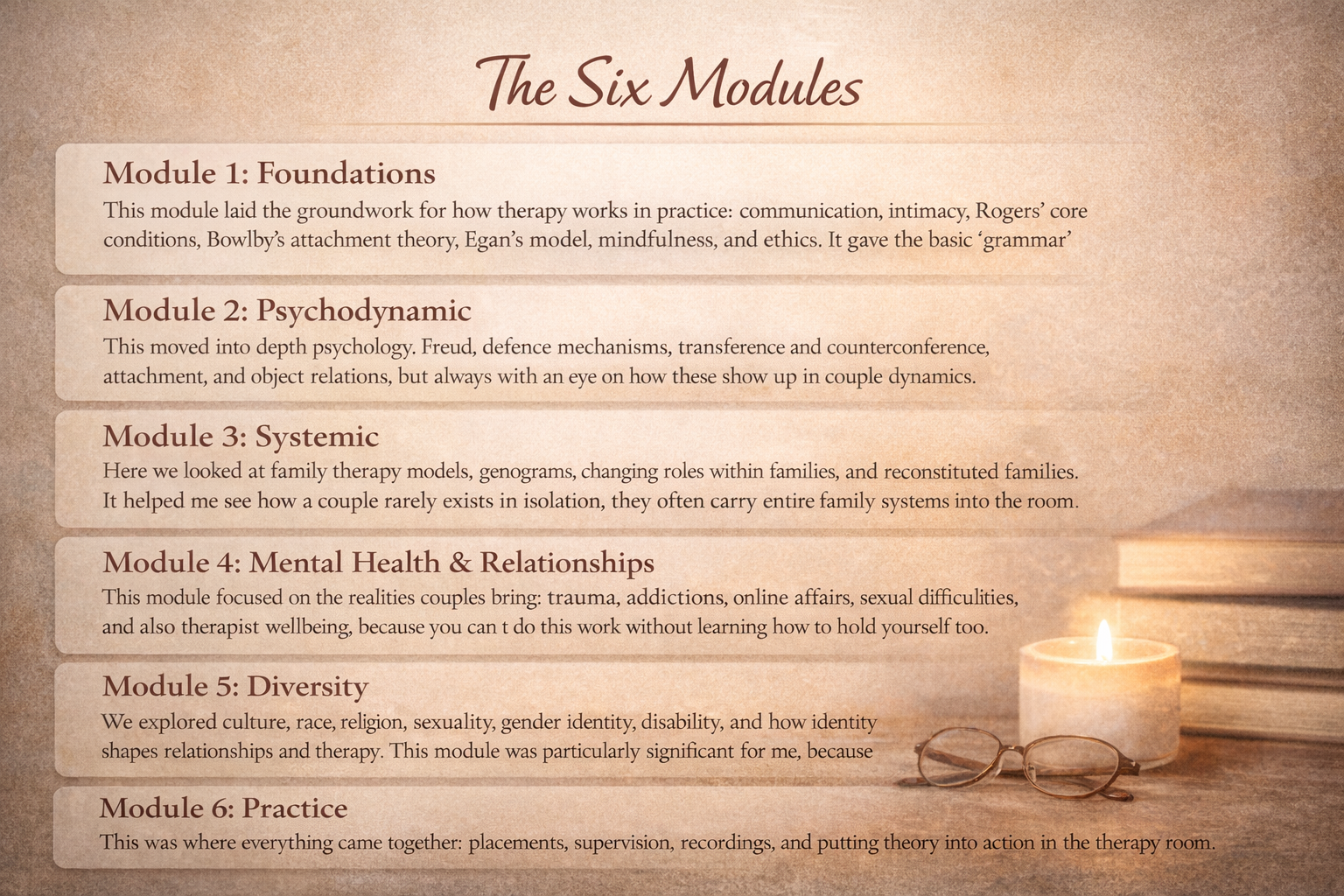

This was a two and a half year programme with Relationships Scotland, the country’s largest provider of counselling and mediation, accredited by Edinburgh Napier University. It was practical, rooted in real family life, and consistently linked theory to what actually happens in the therapy room.

Each module included essays and reflective pieces. For the final module, I wrote a case study applying theory to practice and the use of supervision. I also presented on menopause and its impact on couples (don’t ask how I got that topic! 😂).

Practice Requirements & Support

This wasn’t just academic. It was deeply practical, with strong support structures:

- 200 hours of counselling practice

- Supervision logs and recorded sessions

- Placements, supervision, and CPD provided in-house

- Main placement: Glasgow office

I was really lucky that everything was in-house. Speaking to others who completed the diploma, they had to find their own placements and pay for their own supervision. For me, everything was in house. I was doing my placement in Glasgow and Argyll and Bute online. Supervision was provided by the organisation, as well as CPD. It was such a great blessing.

From Training to Practice

I started in 2019 and finished in 2022. Those years were full. I lost my grandmother, we welcomed two more children, and I juggled chaplaincy, teaching, interfaith work, and family life. Finances were tight and then Covid hit.

Online training was hard. Counselling training is interactive and experiential. Thankfully, only the final module was online. Most of our learning was face to face. I still feel counselling training should be in person. It is something you feel, not just study.

Submitting recordings, supervision logs, and placement hours was a huge relief. I qualified. From a class of twenty, I was one of only two men and the only Muslim, the only brown face in the room.

When my certificate arrived, I was overjoyed. My wife made me promise no more big study commitments for a while. I registered with BACP and officially launched Healers Muslim Counselling, which I had begun during training with free sessions. Qualified now, I chose to continue and alhamdulillah, I have never regretted it.

My tutor told me “Be grateful to your clients, you will learn far more from them than they will learn from you.”

Why Healers Exists for Muslim Clients

Whilst training, I often thought about how Muslims experience non-Muslim counselling spaces. Sometimes there is relief in speaking to a stranger outside the community, someone who will not judge. But our morality and outlook do not always sit comfortably in the wider therapeutic culture.

In my experience, the counselling and mental health field is often left leaning. Muslims are accepted, but sometimes only insofar as they also accept certain assumptions. I witnessed this tension first hand.

It struck me as ironic that while counsellors emphasise boundaries in therapy, they sometimes mock or dismiss religious boundaries as nonsensical. In my training, a well-known trainer recommended masturbation for self-soothing. I mentioned that some clients are Muslim and take their faith seriously. He replied, “What kind of religion would stop you from that. Tell them it is silly and they should try it.”

That experience highlighted two issues Muslims can face in therapy. The first is congruence. How genuine can a counsellor be if they see a client’s faith as silly. Carl Rogers described congruence as being real and authentic in the therapeutic relationship. If a counsellor privately rejects religion, it is hard for that not to leak into the space.

The second is suspending judgment. Petruska Clarkson describes this as the ability to set aside one’s own values to truly see the client’s world. Without it, empathy becomes limited and the space can feel unsafe.

When these are missing, a Muslim client may end up feeling judged, misunderstood, or even treated as the problem because of their faith.

I felt this is where Healers could play an important part. As a traditionally trained scholar, people naturally felt comfortable with me. I leave the scholar hat at the door, but clients are reassured I will not advise anything absurd. The spiritual element matters to me, even in a formal therapeutic setting. I often end sessions with, “Inshallah, lots of duas for you.”

I still remember one client who asked me to end every session with a dua. For him, it was deeply meaningful, closure that felt congruent with his faith and values. For many Muslims, spirituality is not separate from healing, it is essential.

Healers has grown considerably. We typically see two broad groups. Individuals seeking support after something difficult, such as bereavement or addiction. And couples, where two patterns recur, major in-law issues, and husbands with a fractured sense of self, including infidelity or hidden addictions to pornography or drugs that finally come to light.

I have noticed Muslim couples often come to counselling later, when problems have built up and the work feels heavier. Many white couples I see come earlier, sometimes almost like a relationship health check. For many Muslims, counselling is still something sought in crisis rather than early intervention.

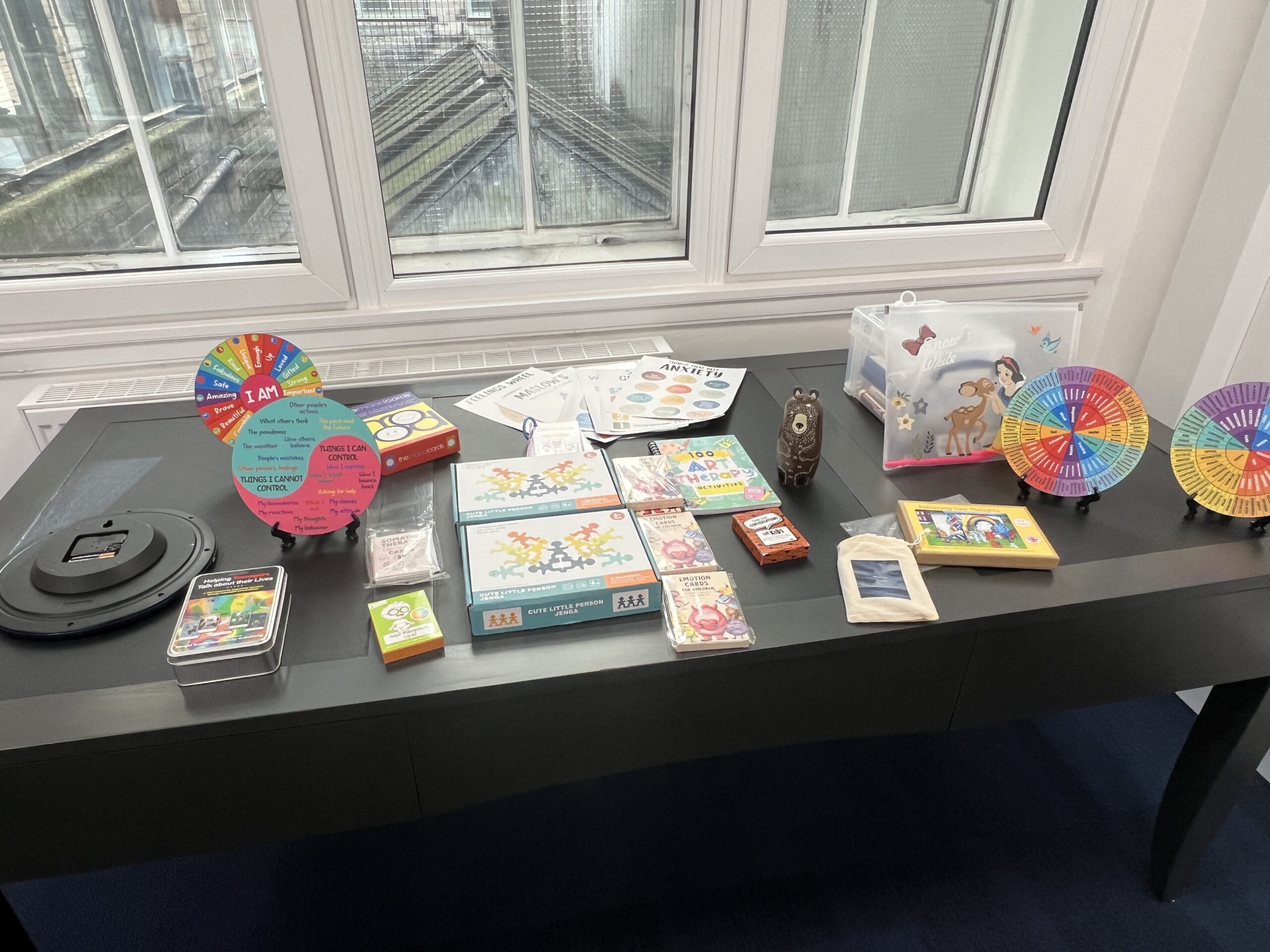

This is an example of a CPD event. CPD is about continuous professional development, and each year I need to show that I am doing this, so I regularly attend CPD events, often led by very experienced therapists.

What I Do Now

From this foundation, my work now spans several overlapping roles.

I work as a Muslim Chaplain at Heriot Watt University. I enjoy it. It often feels like informal counselling, and the skills transfer well. My office is in the Wellbeing Centre alongside student counsellors, so I am close to the work they are doing and regularly attend wellbeing meetings. I also lead the weekly Juma prayers.

I also work with Relationships Scotland, the largest organisation for counselling, therapy, and mediation in Scotland. I typically see three to five clients a week. Being part of the organisation gives me regular CPD, high quality supervision, and a supportive professional network. Most of the couples I see there are white, which is a little break from my Muslim clients.

Healers is more full on. I see around eight to twelve clients a week, often in the evenings to suit couples with children. The work can feel heavy but deeply meaningful. I keep sessions affordable to make them accessible for Muslims. That has always been a core aim.

Although these roles look different, for me they feel like different expressions of the same work, each shaping how I listen, reflect, and support people in the others.

Alongside this, I have a private practice. Clients find me through the BACP directory or reach out directly. Many are Muslim but not very practising. I remember a couple who said they had left Islam but still held deep respect for it. It made me reflect on why they chose me. Perhaps something about faith, familiarity, or being understood still felt safe.

For my own development, I meet monthly with a supervisor who was my tutor during my diploma training. She has an incredible depth of theory, which I value. I attend trainings and CPD to stay current and read Therapy Today, the BACP magazine. I am registered with BACP and work within its ethical framework, and yes, I read a lot of books.

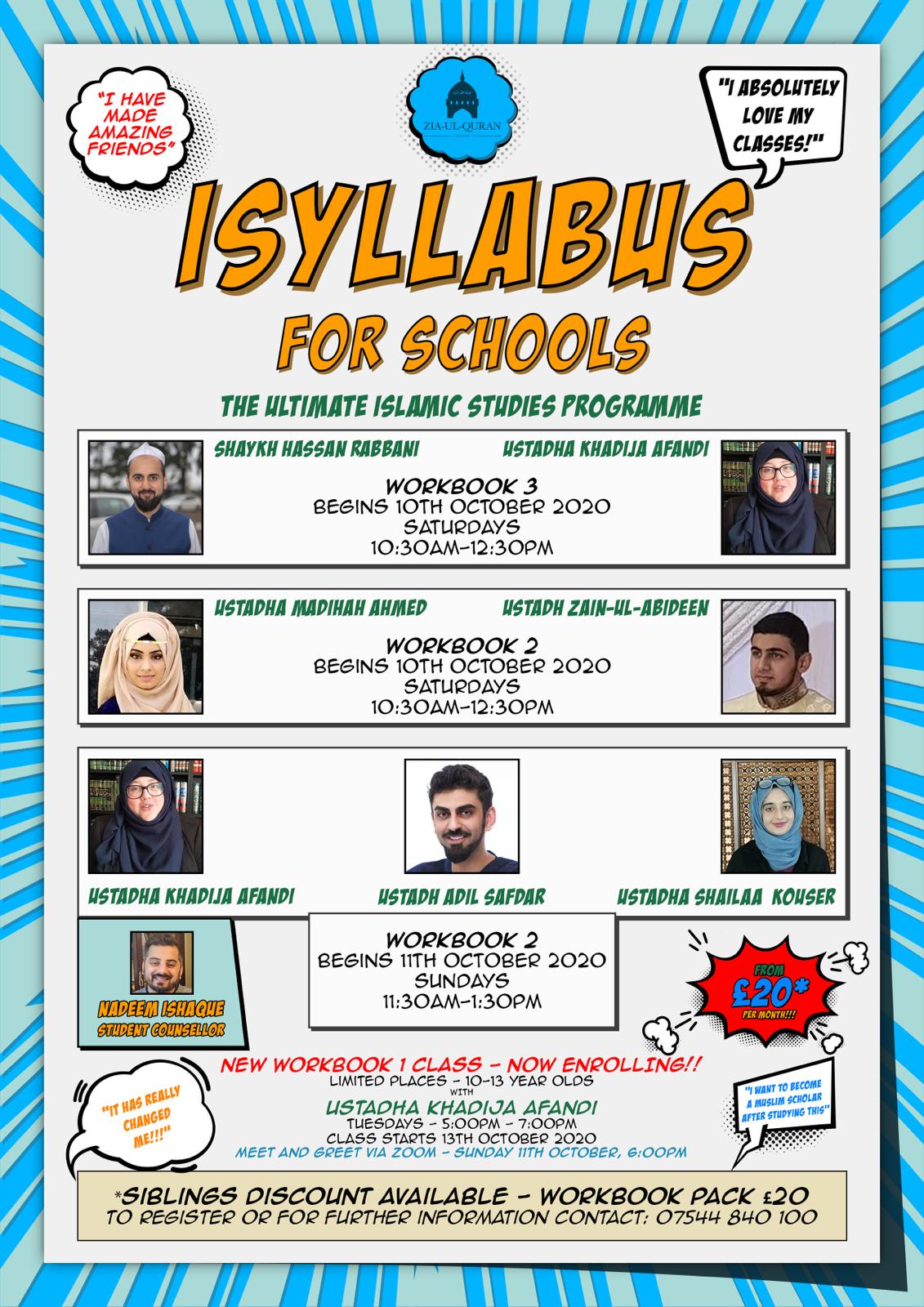

Young People

For almost a decade now, I have been engaged in educating Muslim teenagers. I have taught across various syllabuses and tried to make the teaching engaging, with weekly Islamic Studies classes taught in a lively environment, taking students on trips, and engaging with parents. The course became popular, and I eventually brought in many teachers, so it also became about managing teachers as well as students. But I never gave up teaching.

From all of this, what I did not expect was for parents to begin contacting me with serious issues affecting them and their children. These ranged from general disobedience to sexual disorientation and other complex issues. Once again, I felt that working with teenagers and counselling them was out of my depth. So I enrolled in another training programme. Of course, my family had to be on board with this, because it meant serious reading, studying, placement, and essays.

This will also allow me to become a school counsellor, which is important to me as someone who works closely with teenagers. The struggle of being a Muslim teenager, especially around identity and belonging, can be very heavy, and I want to be better equipped to support them.

Children & Young People Counselling

In 2025, I enrolled in the BACP Approved PDA in Counselling Children and Young People (10 to 18), a qualification designed for already trained counsellors and therapists and broadly equivalent to Master’s level study. It is specifically aimed at developing the skills and confidence needed to work ethically and effectively with young people.

The course ran over twelve weeks, with in person teaching every Wednesday. This made Wednesdays especially intense for me. I would start the day with clients from 7 to 8am, then catch the train into Glasgow Central for a full day of training. After the training finished, I would travel straight to Pollokshields to teach the teenage Islamic Studies class for two hours. Immediately after that I would see another client, then catch the train home and usually arrive back around 10pm. It did not help that on Tuesdays I was in Edinburgh all day as well, so this routine definitely had an impact on family life.

The course itself was highly experiential and engaging. A major focus was on ethics, safeguarding, and professional responsibility, which is probably the most important aspect of working with children and young people. We looked in depth at consent, confidentiality, risk, and professional boundaries, and how these operate differently when the client is a minor.

We also learned a range of play and creative techniques, because many children and young people struggle to articulate what they are feeling in words. This requires a very different approach from adult therapy, where verbal reflection is often easier. We explored how developmental stage, attachment, family context, culture, and social pressures shape a young person’s inner world and emotional life.

The formal teaching element finished in December 2025, including the academic writing, reflective evaluations, and readiness for practice process. In 2026, I will be completing the required 50 hours of supervised placement, working across various secondary schools in Glasgow.

This training matters deeply to me. I have spent many years working with Muslim teenagers, and I see first-hand how complex and heavy the struggle of adolescence can be, especially around identity, belonging, faith, and culture. I wanted to be properly equipped, ethically, psychologically, and professionally, to support them well.

It has been demanding, both practically and emotionally, but it feels like a natural continuation of the work I have already been doing.

How Many Hats Do I Wear?

I want to conclude by asking, have I left my Azhar studies and turned away from my traditional learning?

People often say I wear different hats, and I would disagree. Different hats sometimes suggests a fragmentation of roles, but for me all my roles are deeply integrated. I am a Scottish trained Azhari scholar, and I always will be. The role of Imam and Shaykh has always been dynamic.

Scholars from the early era learned different languages. Scholars in the Ottoman period were often well-versed in Latin and Greek, because the Ottomans had absorbed large Byzantine populations and engagement with them was necessary. I can imagine those scholars also being well-versed in Christianity and its scriptures, because understanding the other mattered.

The Sahaba too learned different languages. The famous hadith scholar Ibn Hajar writes in al Isabah fi Tamyiz al Sahabah, in his entry on the great Companion Zayd ibn Thabit, that he was instructed by the Prophet ﷺ to learn the languages of other communities for practical and ethical reasons. Zayd relates that the Prophet ﷺ asked him to learn Hebrew, and in another report instructed him to learn Syriac, the language used by Christian communities. Zayd learned these languages quickly and then served as the Prophet’s translator.

We also see this pattern later in figures like Ibn Khaldun, who was not only traditionally trained, but also became a sociologist, historian, and economist in order to understand how societies function, rise, and decline. His work shows that engaging with new disciplines was never seen as leaving the tradition, but as deepening its ability to speak to reality.

I believe that our language today is the language of empathy, or more broadly, mental health. I feel that my training over the years has not taken me away from my traditional scholarship, but has further integrated me into it. The path of learning and evolving still continues.

Hassan Rabbani

January 2026

If you’re in Scotland, the usual starting point is the COSCA Counselling Skills Certificate. It’s a one-year, part-time course that helps you learn basic listening and relational skills and see if the work suits you. After that, you can apply for a full diploma in counselling, psychotherapy, or relationship counselling.

I chose the Diploma in Relationship Counselling with Relationships Scotland because it covers both individual and couple work. It runs over two and a half years and is very practical, with real client work, supervision, and reflective learning, which suited the kind of work I wanted to do.

What I offer is professional counselling and therapy, not religious rulings or instruction. I work within a formal ethical and professional framework, but I also respect and understand faith, and I do not treat a client’s religion or values as something to be dismissed or corrected.

In therapy, people are not confessing in a religious sense, they are speaking honestly in a private and confidential space to understand themselves and change. I do not judge or shame what is shared, and I only break confidentiality if there is a serious safety risk. The aim is to support insight, responsibility, and growth, not to normalise harm or pass moral judgment